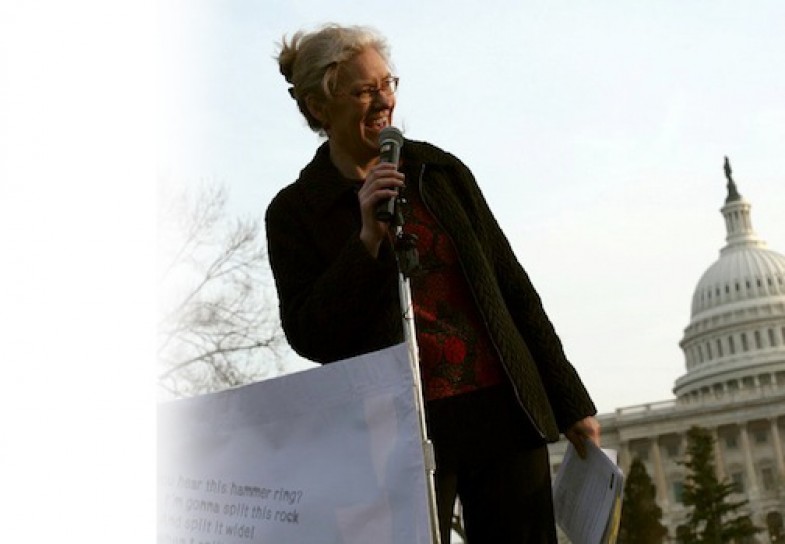

Sarah Browning is the executive director of Split This Rock, a national organization that helps poets take a greater role in public life and heightening poetry as a living, breathing art form. Split This Rock integrates the poetry of provocation and witness into movements for social justice and supports poets of all ages who write and perform this vital work.

Browning is on the team of poet advisors that will guide Commons Magazine’s new poetry project. I recently spoke with her about poetry’s role in progressive activism and its ability to advance the commons movement.

— Camille Gage, On the Commons artist in residence

What drew you to a life in poetry?

Oh, what a great question. It’s also a hard one. There was a moment in my life when I thought if I wasn’t writing I would just curl up and die. That was when I had been an activist for ten years without also honoring my own voice and nurturing my creative self. It seems like that happens too often to activists. It was very much happening to me.

For some reason poetry had grabbed me at some point—maybe it was when I realized that I wasn’t going to become a musician, which was what I first loved. I still love to sing, but I have a terrible sense of rhythm. In poetry you can indulge that idiosyncrasy, in music not so much!

Do you have a favorite historical poet?

Walt Whitman, whom I call “the uncle of us all.” He was the first poet in the United States to really plumb the crazy variety of American experience. It doesn’t mean he told everyone’s story, not by a long shot. He was also a creature of his time, but he was “in the world.” All of his poetry is ‘in the world’ in a way that I admire tremendously. He just had a wild imagination. Every line keeps giving and giving. Walt Whitman you can return to year after year, week after week, and he always gives you something new.

How did you become involved with Split This Rock? Can you talk about poetry’s role in progressive activism?

Split this Rock has its roots in the DC Chapter of Poets Against the War, which began at the start of the invasion of Iraq as part of the international uprising to try to prevent that war. At the time it was the largest mobilization of poets ever. I had just moved to DC and didn’t have a poetry community here yet, so the call to build poetic resistance came at an excellent time. It gave me a chance to reach out to fellow poets in DC.

I built a strong local chapter, and being in the capital we had all sort of opportunities for speaking out. We built on a tradition I was lucky to learn about, a tradition of activist poets, primarily African American poets, in DC. They have been very engaged in the public life of the city and of the nation from the nation’s capital.

The response from poets was tremendous and the response from the public was always very moving. People who’d never been to a live poetry event before came because of the topic. Activists who felt deeply disheartened were coming to our events and feeling some of their hope for change restored.

After several years of this kind of intensive and very powerful organizing locally we realized we had both the responsibility, being in the nation’s capital, and the opportunity to do something on a larger scale. That’s when we dreamed up the first Split This Rock poetry festival in 2008, which we timed to coincide with the 5th anniversary of the war in Iraq. That was the first national gathering of its kind that named and honored and celebrated poets who also considered themselves activists and public citizens. It was deeply transformative.

Poetry had been a very conservative field for a long time, the last holdout of extreme white-a-tude. Its been a very conservative field for a long time. Those outside of that tradition because of their race or gender or their engagement had felt heretofore very isolated. People said to me at that first festival, “I’ve waited my whole life for something like this.”

That’s amazing. Because of my background and personal lens I strongly associate poetry with activism.

In cities like DC or Minneapolis, and within specific communities like the Chicano activist community or the Black arts or feminist movements, of course there have always been activist poets. But those poets were deeply alienated from the establishment poetry world. The major houses or prestigious journals didn’t publish them, and they didn’t receive the major prizes or get the university appointments. Much of that is finally beginning to change. It’s very exciting and gratifying. Establishment poetry is finally beginning to look like, and sound like, American poetry.

I think the impact of the kind of poetry you are familiar with, and that Split This Rock celebrates and promotes, is that it helps tell the story of what it means to be alive today in all its variety. If we just look to media, or, God forbid, to those that are supposed to interpret events for us, like the talking heads on television, we get a very narrow notion of the American experience. Poetry helps us understand the great richness and variety of our lives. It also revitalizes our language at a time when language is used to pacify the population—by using, essentially, the tools of propaganda. Creating new language, and repeating it often enough, makes us feel sedated. It also points out the injustices that we are sometimes blinded to because we’ve become numb to them.

Yes! The use of language to manipulate public opinion has been raised to a high art. I’m thinking about people like Frank Luntz, who did so much to refine the contemporary use of language for propaganda for conservatives, framing their agenda with phrases like, ‘family values.’

Language helps us create meaning. A simple example is how activists in the gay rights movement have done an excellent job shifting the language from gay marriage to marriage equality. When you say “gay” marriage it sounds like its something special for gay people. But when you say marriage equality it shift the meaning to equal rights, which is what it is.

Similarly, in the other direction, if you say ‘stress positions’ long enough it makes you think torture might not be so bad. But it’s not a ‘stress position’—it’s torture. Poetry can provide the kind of vivid imagery to remind us of the injustices of our world. At the same time it also helps us imagine the world we want to create.

How do you think poetry advances the commons?

The commons is about navigating and negotiating what we have in common. What we share as humans. Poetry helps us understand what it is we share with others who we’ve been told are radically different from ourselves. Poetry can help us bridge those differences. It can also show us the differences that do exist and help us understand them.

Poetry in all its variety, idiosyncrasy, and wild creativity also wakes us up to the richness and power of our language that belongs to everyone.