The only effective answer to organized greed is organized labor.

Thomas Donohue, Former President AFL-CIO

In the early 1980s Ricardo Levins Morales, an artist and labor activist in Minneapolis designed a bumper sticker with a simple eight-word message, “From the people who brought you the weekend. “ Since then, he’s sold tens of thousands. In 2007 Ricardo told National Public Radio he often found people “squinting with puzzled looks at the stickers.” “For people who are not steeped in labor history,” he added, “it might take a few minutes to figure out what on earth they are talking about” because most people think the weekend has always been here, “like the weather.”

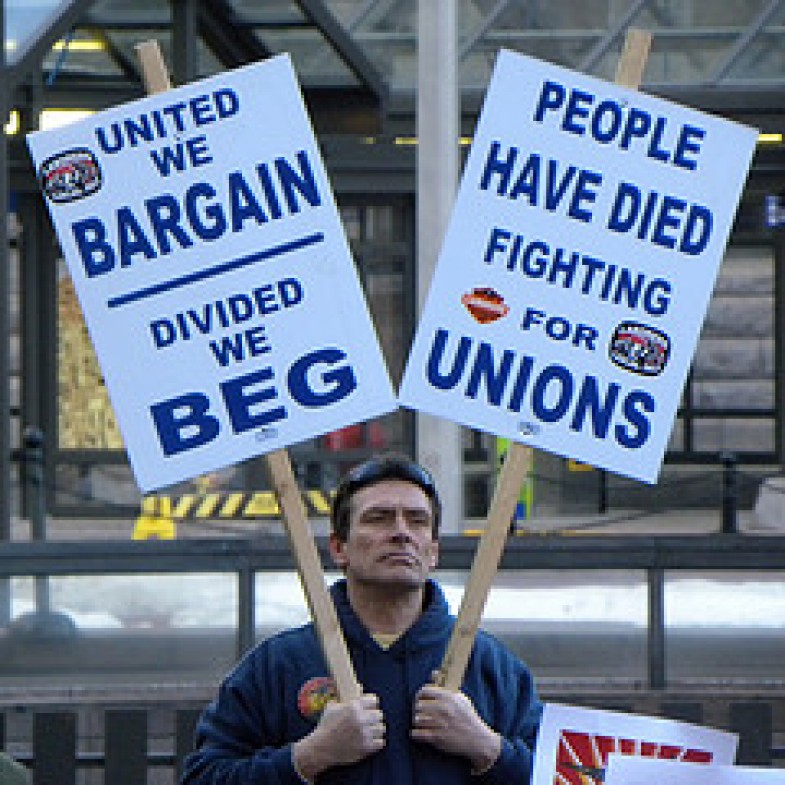

No Virginia, the weekend has not always been here. At the end of the 19th century men, women and children often worked 10 to 16 hour days, seven days a week. The weekend, along with the 8-hour day, rest breaks, decent wages and working conditions were gained only over decades, and at great human cost. And the vehicle used to win these advances was the union.

In the last generation, US unions have shrunk in size and influence, largely as a result of a withering attack by corporations and Republicans. And with that shrinking influence has come a corresponding decrease in the standard of living of most Americans. Indeed, as we shall see, the correlation between the strength of unions and the strength of the middle class is so empirically strong it might well be considered causal.

A Brief History of the Rise and Fall of US Labor Unions

In the decades after the Civil War American industrialization came to America. Railroads criss-crossed the continent. Markets went national and international. Factories swelled to fantastical size. One or two companies dominated their industries. Workers were pushed to their limit and beyond. Sometimes their pent up anger and frustration exploded into huge labor uprisings. And when they did, corporations, governments and courts retaliated.

“In the centers of many American cities are positioned huge armories, grim nineteenth-century edifices of brick or stone,” Jeremy Brecher’s classic book, Strike begins, “They are fortresses, complete with massive walls and loopholes for guns. You may have wondered why they are there, but it has probably never occurred to you that they were built to protect America not against invasion from abroad but against popular revolt at home. Their erection was a monument to the Great Upheaval of 1877”.

The 1877 general strikes brought work to a standstill in a dozen major cities. In communities across the nation strikers took over authority. (To read more about the general strikes not only of 1877, but 1919 and 1934 get a copy of Strike from South End Press.)

In the late 19th century, giant corporations built a private police force to spy on workers and when needed, knock them about. “(B)usinessmen saw the need for greater control over their employees”, historian Frank Morn writes, “their solution was to sponsor a private detective system. In February 1855, Allan Pinkerton, after consulting with six midwestern railroads, created such an agency in Chicago.”

At one point the Pinkerton Detective Agency employed more men than the U.S. Army. And when the Pinkertons were not enough, Governors called in the National Guard, a tradition Wisconsin Governor Walker recently threatened to revive if public employees become restive. And when the National Guard was not enough, the army intervened. The general strikes of 1877 were finally put down with the assistance of 10,000 US troops.

The courts were firmly on the side of the corporations even when it came to perverting the plain text of a law. In 1890, for example, Congress passed the Sherman Antitrust Act clearly aimed at prohibiting abusive industrial monopolies. In 1895, the Supreme Court effectively gutted the Act’s primary purpose when it ruled that the American Sugar Refining Company had not violated the Act despite controlling approximately 98 percent of all sugar refining in the U.S. How could that be you might ask? The Court explained that manufacturing is not trade! Therefore monopoly control of manufacturing could not be considered a restraint of trade.

Giant manufacturing firms engaging in price fixing were innocent of restraining trade, the courts decided. But unions who tried to bargain on behalf of the firm’s workers were guilty.

Corporations argued, and the courts agreed that unions were interfering with a Constitutionally protected right to contract free of government interference. Employers were free to discourage employees from joining unions. One of the most common methods used was to require employees to sign what became known as “yellow-dog contracts”. The employee agreed not to join a union, to quit a union if already a member, and to be fired if they did not comply with the contract. In 1908, the Supreme Court gave its seal of approval to yellow-dog contracts, citing the need to protect the “liberty of contract” no matter how wildly imbalanced the power of the two negotiating parties.

The Great Depression brought mass unemployment, unilateral wage reductions and renewed labor uprisings. But this time the outcome was different because workers had a sympathetic ear in Washington. In 1935 the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) required employers to bargain “in good faith” and proscribed “unfair labor practices”. Most importantly, the Act invested the National Labor Relations Board with powers of enforcement.

In April 1937 the Supreme Court upheld the NLRA but only by the thinnest of margins, 5-4. For the first time the Court supported a major New Deal law. Most observers believe the vote of the fifth Justice was gained only because the decision took place a few weeks after FDR, on the heels of an overwhelming electoral victory in 1936, introduced “court packing” legislation designed to stop the Supreme Court from continuing to obstruct New Deal legislation. Historians have called the historic turnaround of the Supreme Court, “the switch in time that saved nine”.

On April 12, 1937, the day the Court upheld the NLRA, labor lawyer James Gross describes the scene at the NLRB. “(I)t was just wild”, a “whole feeling of victory…ran through the office…[it was] like a carnival almost for that day and days afterward.”

A tsunami of organizing swept over the country. Between 1935 and 1945 8 million new workers joined unions, tripling overall union membership.

Corporations quickly counterattacked. In 1939, Southern Democratic Congressman Howard Smith established a special Committee to Investigate the National Labor Relations Board and held a series of highly publicized hearings designed to vilify the NLRB. In 1940 he introduced a bill that would have overturned much of the Wagner Act. The bill passed the House by a two to one margin but failed to get out of a Senate Committee. Nevertheless, the bill and the hearings did have the almost immediate affect of making the embryonic NLRB more cautious and politically sensitive.

In 1948 the Republicans gained control over both houses of Congress. One of their highest priorities then, as now, was to weaken the newly gained power of organized labor. The Taft Hartley Act was their legislative vehicle for doing so. The Act, passed over a veto by President Truman effectively stripped labor unions of many of their most progressive voices, leaders who viewed labor organizing as a part of a much larger national social movement for justice and equality. The Act outlawed sympathetic strikes, making it illegal for workers to substantively demonstrate their solidarity.

And most important of all, the Taft Hartley Act allowed states to enact laws that banned union shops, that is, shops where if a union was voted in all workers had to be part of the union and pay dues. In these states, even if a union were certified by a majority of the workers, the workers did not have to belong to the union or support its work (including a strike fund). Several southern states immediately enacted what they called right to work laws. Today 22 states have such laws. In these states, union density has rarely exceeded 10 percent, even when union membership overall was at its peak in the 1950s.

Despite the restrictions of the Taft Hartley Act, labor unions continued to expand in the post war era. By the late 1950s almost 40 percent of the private workforce was in unions. Unions were widely seen as playing an important role in society. As Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower asserted, “Only a fool would try to deprive working men and women of their right to join the union of their choice.” Indeed, as late as 1977, even conservative columnist George Will would concede, “I think American labor unions get a large share of the credit for making us a middle-class country.”

But in 1980, Ronald Reagan came to office, and the future of unions, and as we shall see, of middle class America, would change. Reagan began his war on labor in the summer of 1981, when he fired 13,000 striking air traffic controllers. Ironically, the air traffic controllers union had endorsed Reagan for President in 1980.

Washington Post columnist Harold Meyerson has described the firings as “an unambiguous signal that employers need feel little or no obligation to their workers, and employers got that message loud and clear — illegally firing workers who sought to unionize, replacing permanent employees who could collect benefits with temps who could not, shipping factories and jobs abroad.”

Reagan appointed three management-friendly representatives to the five-member National Labor Relations Board. Donald Dotson, Reagan’s choice for Chairman, confirmed by Congress, publicly expressed opinions that would have been right at home in 1890: “unionized labor relations have been the major contributors to the decline and failure of once-healthy industries” and have resulted in the “destruction of individual freedom.”

Under Reagan, the NLRB settled only about half as many complaints of employers’ illegal actions as it had during the previous administration of Democrat Jimmy Carter, and those that were settled upheld employers in three-fourths of the cases. For comparative purposes, even under Republican Richard Nixon, employers won only about one-third of the time before the NLRB.

Reagan’s NLRB took an average of three years to rule on complaints and generally, when ruling against the employer, did no more than order the discharged unionists to be reinstated with back pay.

The combination of a government that gave the green light for corporate union busting and corporations who enthusiastically took advantage of that opportunity, led to a rapid decline in union membership. Today private sector union membership levels are back to 1900 levels, the era of yellow dog contracts and illegal collective bargaining.

The only reason union membership has remained even modest has been because of the rise of public employee unions.

Government employees were not covered by the Wagner Act and, without the ability to bargain, their living standards fell further behind their private sector counterparts. In the 1950s and 1960s these workers pushed for collective bargaining rights. In 1959 Wisconsin became the first state to grant this right to public employees.

State and local public employee unions burgeoned in the next decades. In 1973, there were almost five times more union members in the private sector than in the public sector. In 2009, for the first time, public sector union membership exceeded that in the private sector. Public sector workers have achieved near parity with private sector workers in pay and benefits.

The struggle to gain public employee bargaining rights was never easy. To this day 5 states explicitly prohibit public employees from participating in collective bargaining. Another 11 allow public employee collective bargaining but do not require it. Josh Marshall at TPM has put together an excellent state-by-state map on the issue.

In some cases recognition of public employee unions came only after violence. This was especially the case in the south if the union leadership was African-American.

In some cases recognition of public employee unions came only after violence. This was especially the case in the south if the union leadership was African-American.

As the 43rd anniversary of Martin Luther King’s assassination approaches we might reflect that he was in Memphis to march with striking sanitation workers. In February 1968 two black sanitation workers had been crushed to death when the compactor mechanism of the trash truck was accidentally triggered.

On February 12, more than 1,100 black sanitation workers began a strike for job safety, better wages and benefits, and union recognition. King’s assassination did not dampen the workers’ resolve. As Taylor Rogers, one of the strike’s organizers recalled, “If you stand up straight, people can’t ride your back. And that’s what we did. We stood up straight.”

The sanitation workers won. Their contract included union recognition, higher wages, a dues check off, and the updating of antiquated sanitation equipment. Another practice that had infuriated black workers—sending them home on rainy days without pay while white supervisors stayed and collected a paycheck—was also ended.

Republicans are now focused on stripping public employee unions of some or all of their bargaining rights or, when they can, gutting their unions.

Wisconsin Was Only The Beginning

The bill recently enacted by the Republican Wisconsin legislature (and currently on hold pending the appeal of a court decision that it was passed illegally), not only strips public employees of the right to bargain collectively, but sharply curtails their union of resources by eliminating the union checkoff. The bill also requires annual elections to recertify the union, elections paid for by the union.

Wisconsin is by no means alone. By the end of March, 18 states had proposed legislation which would remove some or all collective bargaining powers from unions. These include Maine, Arizona, Indiana, Alaska, Michigan and Ohio.

At the federal level, a Republican bill, HR1135, would make an entire family ineligible for food stamps if one of its members were on strike. A record 42 million Americans now receive food stamps.

In late March, Republican-dominated Michigan became the first state to reduce unemployed benefits, lopping off an astonishing 6 weeks from its current maximum of 26 weeks. Republican legislatures of Arkansas, Florida and Indiana may soon follow suit.

Republicans have also targeted University labor studies departments or individual professors who have spoken out in favor of unions. In late March, Republicans retaliated against William Cronon, a renowned historian at the University of Wisconsin, demanding copies of all e-mails sent to or from Mr. Cronon’s university mail account containing any of a wide range of terms, including the word “Republican”.

Cronon’s sin was in publishing an opinion piece in The Times suggesting that Wisconsin’s Governor has turned his back on the state’s long tradition of “neighborliness, decency and mutual respect.” Professor Cronon is best known for his astonishing book, Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West, which won the Bancroft Prize for best work of American history that year and was one of three nominees for the Pulitzer Prize in History.

Almost simultaneously, Republicans filed Freedom of Information Requests for material from professors at the University of Michigan, Michigan State and Wayne State University. The breadth of the request to the University of Michigan’s Labor Studies Center is typical: “all electronic correspondence carried out to or from employees, contractors, etc. of the University of Michigan Labor Studies Center in which the following terms (or their derivatives) appear: ‘Scott Walker’, ‘Wisconsin’, ‘Madison’, ‘Maddow’. Any other emails that deal with the collective bargaining situation in Wisconsin.”

Republicans are not only targeting labor studies professors. They are attempting to expunge the already regrettably rare places in the United States where labor history and unions are viewed in a positive light. The New York Times reports that Maine’s Republican Governor Paul LePage has demanded a 36 foot-wide mural on the Department of Labor’s building be removed. “The three-year-old mural has 11 panels showing scenes of Maine workers, including colonial-era shoemaking apprentices, lumberjacks, a “Rosie the Riveter” in a shipyard and a 1986 paper mill strike. Taken together, his administration deems these scenes too one-sided in favor of unions.” Reporter Steven Greenhouse adds, “Mr. LePage has also ordered that the Labor Department’s seven conference rooms be renamed. One is named after César Chávez, the farmworkers’ leader; one after Rose Schneiderman, a leader of the New York Women’s Trade Union League a century ago; and one after Frances Perkins, who became the nation’s first female labor secretary in 1933 and is buried in Maine.”

Those who know labor history know that Governor LePage’s effort to Rose Schneiderman and Frances Perkins came almost 100 years to the day after the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in New York City, the deadliest disaster in the history of that city and the fourth deadliest of any industrial accident in US history.

Could Governor LePage’s Audacious Actions Make For A Teachable Moment?

It would be altogether fitting to use LePage’s actions as a teachable moment for the people of Maine and the nation about the context and consequences of the Triangle Shirtwaist fire and the role people like Ms. Schneiderman and Ms. Perkins played in improving the quality of life for all of us.

At the turn of the 20th century, the garment industry was New York’s best known and by far its largest. In 1910, 70 percent of the nation’s women’s clothing and 40 percent of the men’s was produced in the City.

The workers in the garment industry were recent women immigrants. Women comprised more than 70 percent of the workforce. About half were teenagers. About half were Jewish.

A normal workweek was 65 hours. In season this might rise to as many as 75 hours. Despite their meager wages, garment workers often were required to supply their own basic materials, including needles, thread, and sewing machines.

Workers could be fined for being late for work or for damaging a garment they were working on. At some worksites, such as that of the largest garment manufacturer, the Triangle Shirtwaist Company, steel doors were used to lock in workers so as to prevent them from taking breaks. As a result women had to ask permission from usually male supervisors to use the restroom.

In September 1909, fed up with the working conditions at the Triangle Shirtwaist factory, workers voted to join a union. Triangle immediately fired those who had organized the vote. In response, the workers at Triangle walked off the job. News of the strike quickly spread. A series of mass meetings were held. Leading figures of the labor movement spoke about the need for solidarity and preparedness. But it was a newcomer, a woman named Clara Lemlich, who electrified the crowd by talking in Yiddish to the largely Jewish crowd about the conditions of the women workers and calling for a general strike of all garment workers. According to the International Lady Garment Workers Union (ILGWU), “The crowd responded enthusiastically and after taking a traditional Yiddish oath, “If I turn traitor to the cause I now pledge, may this hand wither from the arm I now raise”, voted for a general strike. Approximately 20,000 out of the 32,000 workers in the shirtwaist trade walked out in the next two days.”

The owners of the Triangle factory met with owners of the 20 largest factories to form a manufacturing association whose primary purpose was to stop unionization. The companies hired men to disrupt the picket lines and physically intimidate the women. New York’s police assisted the companies by arresting 700 women, charging them with various crimes including vagrancy and incitement. Nineteen were sentenced to time in a workhouse. One judge in sentencing a picketer declared, “You are striking against God and Nature, whose law is that man shall earn his bread by the sweat of his brow. You are on strike against God!”

A group of wealthy women, including Frances Perkins, bailed the women out of jail, picketed with them and intervened with officials on their behalf.

Public opinion turned against the manufacturers association. Fearing that the strike would extend into the fashion season, the manufacturers association agreed to arbitration. In early 1910 the women won higher wages, shorter hours and better working conditions. But they refused to recognize the union.

Rose Schneiderman was an active participant in what came to be known as the Uprising of the 20,000. Her family migrated to New York’s Lower East Side in 1890. Her father died in 1892, leaving the family in desperate poverty. Rose and her brothers spent a year in an orphanage before their mother could reunite them. She began organizing women factory workers in 1903. By 1908 she had become vice president the New York branch of the Women’s Trade Union League. She subsequently became its national president for more than 20 years. Later she became a member of FDR’s “brain trust” and worked as a Secretary of the New York Department of Labor from 1937 to 1944. She was a founding member of the American Civil Liberties Union.

Schneiderman was an active campaigner for women’s suffrage. She helped pass the New York state referendum in 1917 that gave women the right to vote in that state.

Schneiderman was an active campaigner for women’s suffrage. She helped pass the New York state referendum in 1917 that gave women the right to vote in that state.

Rose firmly believed that the right to vote was an essential element in achieving economic rights and security for working people. And her experience working in and organizing women in sweatshops held her in good stead when she debated opponents of women’s suffrage.

When a state legislator warned in 1912, “Get women into the arena of politics with its alliances and distressing contests—the delicacy is gone, the charm is gone, and you emasculize women”, Schneiderman retorted:

We have women working in the foundries, stripped to the waist, if you please, because of the heat. Yet the Senator says nothing about these women losing their charm. They have got to retain their charm and delicacy and work in foundries. Of course, you know the reason they are employed in foundries is that they are cheaper and work longer hours than men. Women in the laundries, for instance, stand for 13 or 14 hours in the terrible steam and heat with their hands in hot starch. Surely these women won’t lose any more of their beauty and charm by putting a ballot in a ballot box once a year than they are likely to lose standing in foundries or laundries all year round. There is no harder contest than the contest for bread, let me tell you that.

Schneiderman is also credited with coining one of the most memorable phrases of the women’s movement and the labor movement of her era:

What the woman who labors wants is the right to live, not simply exist — the right to life as the rich woman has the right to life, and the sun and music and art. The worker must have bread, but she must have roses, too.

Her phrase Bread and Roses was later used as the title of a poem and still later was set to music by Mimi Farina and sung by artists as varied as Ani Defranco, Judy Collins and John Denver.

Frances Perkins was born to a middle class family in Boston. She later taught high school chemistry and volunteered in settlement houses in Chicago. She moved to New York and at the beginning of the 1900s Frances Perkins worked to help young women forced into prostitution by predatory landlords and employers and later worked with elected officials to change the conditions that led to these kinds of situations.

In 1910 she was General Secretary of the National Consumers League in New York and had established herself as an expert in industrial working conditions. She was also, like Rose Schneiderman, an active proponent of women’s rights. When she married in 1913, she kept her maiden name, going to court to defend her right to do so.

Frances Perkins was an eyewitness to the Triangle Shirtwaist first of March 25, 1911. More than 145 workers died in that fire. They could not escape the burning building because the managers had locked the doors to the stairwells and exits to ensure the mostly female labor force stayed at their machines.

Speaking at Cornell’s College of Industrial and Labor Relations in 1964 where she was a Professor, Frances Perkins remembered that night:

I happen to have been visiting a friend on the other side of the park and we heard the engines and we heard the screams and rushed out and rushed over where we could see what the trouble was. We could see this building from Washington Square and the people had just begun to jump when we got there. They had been holding until that time, standing in the windowsill, being crowded by others behind them, the fire pressing closer and closer, the smoke closer and closer…They began to jump. The window was too crowded and they would jump and they hit the sidewalk…Every one of them was killed, everybody who jumped was killed. It was a horrifying spectacle.

Perkins later called March 25, 1911 “the day the New Deal began”. She worked on industrial reform legislation. New York established the New York Factory Commission in response to the Triangle Fire and Perkins served on that Commission. Perkins served on that Commission, testified before the state legislature and insisted that lawmakers visit factors and workers’ homes to see firsthand their working and living conditions. New laws and codes were written to protect workers, compensate them for injuries incurred while on the job and to limit working hours for women and children.

Perkins later called March 25, 1911 “the day the New Deal began”. She worked on industrial reform legislation. New York established the New York Factory Commission in response to the Triangle Fire and Perkins served on that Commission. Perkins served on that Commission, testified before the state legislature and insisted that lawmakers visit factors and workers’ homes to see firsthand their working and living conditions. New laws and codes were written to protect workers, compensate them for injuries incurred while on the job and to limit working hours for women and children.

In 1918, Perkins accepted Governor Al Smith’s offer to join the New York State Industrial Commission, becoming its first female member. She became chairwoman of the commission in 1926. In 1929 the newly elected New York governor, Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Perkins as the state industrial commissioner. Perkins led New York to expand factory investigations, reduce the workweek for women to 48 hours, and introduce minimum wage and unemployment insurance laws.

In 1933, FDR made Frances Perkins the first woman cabinet officer in US history, serving as Secretary of Labor. She is widely viewed as the moral driving force of the New Deal and was largely responsible for the introduction of Social Security in 1935 and the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938. The latter immediately raised wages, shortened work hours and in many industries prohibited the use of child labor.

Late in life, Frances Perkins wrote about the maturation of social thinking during the first half of the twentieth century, “Very slowly there evolved…certain basic facts, none of them new, but all of them seen in a new light…it had not been generally realized that on the ability of the common man to support himself hung the prosperity of everyone in the country.”

Unlike in Maine, the US Department of Labor in Washington DC didn’t name a room after Perkins. They named the entire building after her. The Frances Perkins Building honors the person most responsible for improving the quality of life and enhancing the personal security of all Americans.

The Decline of American Unions Parallels the Decline of the American Middle Class

Organized labor has played an important role in making American society more just. As President Jimmy Carter noted, “Every advance in this half-century-Social Security, civil rights, Medicare, aid to education, one after another-came with the support and leadership of American Labor.”

Martin Luther King Jr. echoed President Carter’s sentiments and cautioned, “In our glorious fight for civil rights, we must guard against being fooled by false slogans, as ‘right to work’. It provides no ‘rights’ and no ‘works’. Its purpose is to destroy labor unions and the freedom of collective bargaining…We demand this fraud be stopped.”

But here we will focus more narrowly, on organized labor’s impact on middle class life in America. As the following charts illustrate, it is no coincidence that the decline of labor’s influence has mirrored the decline of the middle class in America.

Since 1980, workers have received a diminishing share of the fruits of their labor. The chart below reveals that before 1980, when manufacturing sector unions represented mover than 35 percent of manufacturing workers, the growth of worker compensation in the manufacturing sector tracked and even modestly exceeded the growth in worker productivity. But after about 1980, as manufacturing union density plummeted, the lines diverged. In the last 10 years, while productivity has risen by about 20 percent worker compensation has barely increased. Today, virtually all additional profits gained from productivity improvements go into corporate coffers not into workers’ pockets.

As union membership has declined, so has the proportion of the national income going to labor. Once again 1980 appears to be the dividing line.

Wages as a share of national income have fallen precipitously while compensation has fallen more modestly, by about 10 percent. Compensation includes pensions and health benefits. In the last 10 years these have slowly and then with increasing speed, been whittle away. Virtually all private sector pension plans no longer guarantee a worker a secure retirement income. Public sector pensions are the subject of intense attack. In both the private and public sector health benefits are being cut back and workers are being asked to reduce their take home pay by contributing more to their health insurance.

While wages and salaries as a percentage of the national income is near its lowest in history, corporate profits are soaring. Corporate profits did take a hit in 2008 but they are now back to their highest level in 40 years. During the same period the unemployment rate more than doubled, and has only recently fallen below 10 percent.

In 2010, the private sector paid out $5.2 trillion in wages and salaries and earned about $1.7 trillion in profits. And 200 US corporations captured almost a third of those profits. US corporations are currently sitting on over $2 trillion in cash right now, much of which is being used to acquire other corporations rather than to invest in new jobs.

The decline of unions has also led to slower growth in income by families. Or more accurately, to slower growth in income by 80 percent of the families. The chart reveals the growth in average family income in two periods: 1947-1973 and 1073-2005. As we see, when union membership was strong, from 1947-1973, income growth for rich and poor families grew at a similar pace. Indeed, the poorest 20 percent of American families saw their annual income grow by significantly more than did the richest 5 percent. In the last 32 years, however, as union membership has rapidly declined, the opposite dynamic has occurred. The income of the wealthiest 5 percent of families has grown eight times faster than the income of the bottom 20 percent.

As union influence has dramatically fallen, income inequality has just as dramatically increased. As the chart reveals, from 1913 to 1929, when unions were weak, income inequality in the United States soared. As union membership swelled after the mid 1930s the gap between rich and poor narrowed, through the early 1970s. And then, when union membership plummeted income inequality levels again rose rapidly. Today they have returned to 1929 levels.

Some might argue that the trends identified in these charts have occurred in many countries. But that would be untrue. After 1980, while American union membership entered a period of rapid decline, union strength increased in must of Europe and Canada through the mid-1990s.

Nowhere is the impact of unions more clearly demonstrated than in the comparison of working life in European countries with very high union memberships with that of the U.S., which has one of the lowest union memberships of any industrialized country as we can see by the chart.

Nowhere is the impact of unions more clearly demonstrated than in the comparison of working life in European countries with very high union memberships with that of the U.S., which has one of the lowest union memberships of any industrialized country as we can see by the chart.

•American workers earn about as much annually as their counterparts in France and Germany and Denmark, but we work almost three months longer.

•US workers, unlike European workers, are not guaranteed at least some paid vacation. Indeed, about a quarter of US workers in the private sector receive no paid vacation at all.

•US workers, unlike European workers, are not guaranteed paid sick leave. Indeed, almost half the US private sector workforce has no paid sick days.

•US workers, unlike European workers, are not guaranteed some form of paid maternity leave.

•If US workers lose their jobs, unemployment benefits pay a much smaller fraction of your wages here than in most countries in Europe and are paid for many fewer months.

The chart shows union density as of 2000. In the last ten years unions in Europe have also been under attack and for many countries these density levels are much reduced, although in all cases they remain significantly higher than those in the US. This, coupled with the economic crisis affecting several European countries, could lead to and in some cases has led to significant attacks on worker benefits.

However, and here we have a very important difference between European unions and the US. In Europe unions and their government partners, have pushed for universalizing benefits rather than tying them to a specific workplace. Thus, as noted above, sick pay and maternity leave and holidays are not the result of individual bargaining with one company or one part of one company. Thus if corporations look to reduce these benefits, the impact will be on all workers.

This is also true of benefits outside the workplace. In the United States, for example, day care is expensive and pre school programs are scarce. In Europe almost all countries offer low cost or free childcare and pre-school programs. This is true whether the family is in a union or not or whether the family members are working on not.

Health care is the outstanding example of this difference between US unions and European unions. In the late 1940s, US unions and corporations began to include health care benefits in their labor contracts. Initially this was a highly controversial development. Indeed, the Supreme Court had to decide whether such benefits could be considered part of collective bargaining under the law. A number of corporations looked favorably on the idea of company based health benefits as a way to reduce the incentive of unions to push for universal health care, which was being vigorously debate at the same time.

Within 25 years employer based health care became the foundation of the US health insurance system. And today, health care benefits are being eroded largely by changes in health benefits within the workplace. Or in a bewildering variety of health care insurance offered for different groups by different levels of government: Medicaid, Medicare, state assistance for uninsured children, etc. Thus when it comes to health care benefits, all Americans are not at all in the same boat.

In Europe, however, unions pushed for universal health care system not dependent on a union contract or employment. Any reductions in the availability of health care proposed by governments today will affect virtually the entire population and thus become much more visible and open to public engagement and influence.

US unions have much to answer for. In the late 1800s, US unions abandoned industry wide organizing for crafts-based organizing. Indeed, the struggles between the AFL, representing crafts unions and the CIO, representing industrial unions, were almost as acrimonious at times as the struggles between unions and management. European unions from the beginning have been broadly based. As discussed, European unions banded together to push for broad and if possible universal benefits. US unions settled for company-based benefits. When several unions represented workers in the same business or industry they famously developed fragmented work rules that hampered efficiencies.

In the last 40 years many US unions have put more energy into territorial battles than into membership expansion. And while still supportive of broader social movements, their abundant financial resources have gone almost entirely into the electoral coffers of the Democratic Party rather than into organizing. For workers (and management) the face of the union is the shop steward and the most interaction is around the grievance process.

Today about half of Americans think favorably of unions. The percentage is about the same for private sector as public sector unions. Interestingly, according to a recent Pew poll, most Americans believe unions improve working conditions for all Americans, but a plurality have been persuaded by corporations that unions have a negative impact on the ability of US companies to compete internationally. The data do not support this relationship. German union members, for example, have better pay and benefits than US union members, but Germany industry remains one of the world’s most competitive. Indeed, while the US runs a huge trade deficit with China, Germany boasts a trade surplus!

Even some Republicans have expressed concern about the decline of unions. Although recently he has been more critical of unions, in the past Utah Senator Orrin Hatch has noted the importance of unions in creating a check and balance on corporate greed: “There are always going to be people [employers] who take advantage of workers. Unions even that out to their credit. We need them to level the field between labor and management. If you didn’t have unions, it would be very difficult for even enlightened employers to not take advantage of workers on wages and working conditions, because of [competition from] rivals.”

In 1991, George Schultz, an economist and former Secretary of Labor under Richard Nixon and Secretary of State under Ronald Reagan, told Leonard Silk of the New York Times that a “healthy workplace” needs “some system of checks and balances”. He believed that unions and an effective “system of industrial jurisprudence” represented that check on corporations’ single-minded focus on the profits. When asked by reporter Leonard Silk why Schultz, who had been president of the Bechtel Group and was at the time director of Bechtel, General Motors, Boeing, Chevron, and the Morgan Bank, would be concerned about the weakness of labor unions. He admitted, “As a management person if I’m running my shop and I don’t have a union, I don’t want them.” But he added, “I’m trying to look at this more broadly and ask a question about where we’re heading…”

In a speech to the National Planning Association, said, “ Free societies and free trade unions go together. Societies are missing something important if they do not have an organization in the private sector, such as a trade union movement” that gives workers the clout labor has exerted to help pass safety and pension laws.”

In 1994 Business Week observed, “unions are often blamed for more trouble than they’ve caused. In the 1970s, for instance, many executives believed that unions inflated prices by lifting wages above some presumed market level. Since then, however, more than 50 quantitative studies have concluded that the higher productivity of unionized companies offsets most of their higher costs.” They quoted Novel laureate Gary S. Becker, a conservative economist at the University of Chicago, “It’s a misreading of economic analysis to conclude that unions inherently cause inflation or unemployment. Some kind of union behavior is bad, but unions that help workers bargain collectively instead of individually perform a legitimate role that’s not counter to social efficiency.”

The uprising in Madison was and is about more than unions. But it was predicated on the proposition that for all their flaws, unions remain the single most important defender of the rights and aspirations of workers. The vast majority of us are workers, that is, we earn our living through our labor (in the case of social security or retirees, through past labor). Unions themselves need to overcome their turf battles and begin to practice a solidarity that has been missing for decades. And all of us need to learn that the best way to protect social gains is to make them universal, for only then does an attack on one become an attack on all. And only then will we fight back to retain our personal security and dignity, not as individuals but as a society.

David Morris is co-founder and vice president of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and director of its New Rules Project. You can follow David at defendingthepublicgood.org